By Uwin Lugoda

By Uwin Lugoda

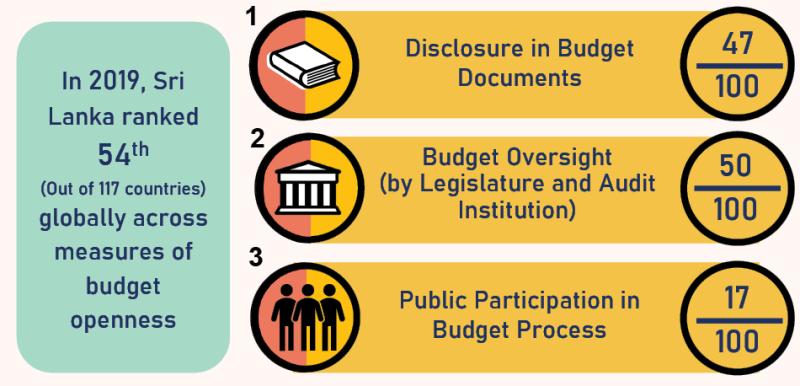

Sri Lanka has been placed 54th out of 117 nations in terms of budget transparency and accountability, according to the Open Budget Survey (OBS) 2019, which was recently released.

The survey, conducted by International Budget Partnership (IBP) is the world’s only independent, comparative, and fact-based research instrument that uses internationally accepted criteria to assess public access to central government budget information, formal opportunities for the public to participate in the national budget process, and the role of budget oversight institutions such as the legislature and auditor in the budget process.

The OBS is conducted every two years, and the 2019 survey showed that Sri Lanka’s score when it comes to budget transparency had increased to 49 out of 100, from the scores of 39 and 44 from the years of 2015 and 2017, respectively.

However, despite this increase in the country’s score, Sri Lanka still falls below the minimum benchmark score of 61, which is needed to be classified as having a “sufficient” level of budget disclosure under international standards.

According to Verité Research Assistant Analyst Lahiri Jayasinghe, the primary aspect the OBS covers is a country’s budget transparency, in terms of the disclosure in budget documents, which is measured by the Open Budget Index. She stated that secondly, the survey covers two smaller elements which are budget oversight by legislature and audit institutions and the public participation mechanisms that are there for the budget process.

As the primary researcher who worked on the survey, Jayasinghe presented their findings to the media on 4 May, via a virtual press conference.

She presented a comprehensive look at how Sri Lanka has performed in each of the three areas, how the scores changed from the last cycle, and what recommendations Verité has for the country going forward.

Transparency

Transparency measures the public’s access to information on how the central government raises and spends public resources.

“When we consider the Budget, the information that is contained in it includes things like what taxes are going to be levied, what kind of expenditure is going to be made for the public; which are decisions that are going to affect the public. So in order to get public engagement in the budget process, there needs to be adequate budget transparency and disclosure of information about the Budget to the public,” said Jayasinghe.

The OBS looks at three main aspects when it comes to transparency: the availability of certain key budget documents, the timeliness of publishing, and how comprehensive the documents are.

Jayasinghe stated that while Sri Lanka has improved its score from 44 from the last cycle to 47 in 2019, putting the country in the category of “limited information disclosure”, the score still does not meet the sufficient standard of information, which requires a minimum score of 61; this indicates sufficient budget disclosure.

“Out of the 117, there are 36 countries in the ‘limited information disclosure’ category with Sri Lanka, but there are also 31 countries that actually meet this minimum score of 61,” she said.

However, the country has managed to score above the global average of 45, and placed third out of the six countries in South Asia which are tracked by the survey. Sri Lanka was only surpassed by Afghanistan, which scored 50 and India, which scored 49, showing that none of the regional countries met the sufficient standard of information.

Sri Lanka’s score has varied over time, depending on both what the county does and does not do in terms of budget transparency. Jayasinghe explained that this also depends on how methodology has evolved over the years and how the international best practices have improved, becoming more stringent.

She stated that the OBS first commenced in 2006, at which time Sri Lanka got a 67 for the country’s performance, and was ranked 13th out of the 94 countries that were considered. She explained that what they can see is that as budget transparency standards and practices improve, Sri Lanka is lagging behind with its standards, while other countries move ahead.

Jayasinghe claimed that one of the biggest reasons the regional countries are yet to achieve a score of 61 is due to the comprehensiveness of the budget documents they publish.

She stated that there are eight key budget documents tracked by the survey when it comes to transparency. These are the Pre-Budget Statement, Executive’s Budget Proposal, Enacted Budget, Citizens Budget, In-Year Reports, Mid-Year Review, Year-End Report, and Audit Report.

Out of these eight, Sri Lanka produced six documents for the 2019 cycle, which was an improvement from the previous year, during which only four were produced. Jayasinghe stated that the country additionally published the Citizens Budget and the Audit Report, which was previously only published for internal use.

Meanwhile, Afghanistan, the best performing country in the region, has produced all eight key documents and has made them publicly available.

Jayasinghe explained that each of these key budget documents that were assessed individually were scored in terms of their content. She stated that out of these, the Enacted Budget scored quite well, scoring 84, while the Executive’s Budget Proposal also performed reasonably well, scoring 60.

However, she stated that the Citizens Budget, 25, In-Year Reports, 33, and Audit Report, 33, had scored poorly in terms of how comprehensive they are when measured against international standards.

When it comes to the Mid-Year Review, Jayasinghe stated that the documents published to the survey were the ones from the Mid-Year Fiscal Position Report, which is done by the Ministry of Finance, and was not considered for the survey because it did not meet the minimum requirements of what is expected by the OBS.

Jayasinghe, together with Verité, recommended that the comprehensiveness of the documents produced should be better and there should also be better consistency across documents.

Taking the Mid-Year Report into account, which comes six months after the implementation, she stated that what the survey requires is a forward-looking projection of the fiscal estimate for the rest of the year, and the revised macroeconomic forecast should be included in the Mid-Year Fiscal Position Report and it should also cover the first six months of the year, because currently, the Mid-Year Fiscal Position Report only covers the first four months.

As for the In-Year Report, she suggested improving its comprehensiveness by disclosing individual actual revenues per individual source, like showing how much revenue is from income tax and how much revenue is from VAT (Value-Added Tax); this way it would give a more detailed picture of where the revenue is coming from. She went on to state that it should also include a comparison of revenue and expenditure either to the original estimate or the figures in the same period for the previous year.

“What this does is it gives you an idea of how well the budget implementation is going because you can track the implementation figures of this year against what was either estimated or what it was in the past,” said noted.

Lastly, Jayasinghe stated that they have seen certain instances where even reports from the same year like the Annual Report and the Mid-Year Report, may not be directly comparable in categories because of the different ways they disclose information. This would create a deficiency in terms of being able to perform an analysis or make meaningful use of that information. Therefore, she suggested that when disclosing any information, data reporting should be done in a consistent format.

Oversight

The OBS also examines the role that legislatures and supreme audit institutions (SAIs) play in the budget process and the extent to which they provide oversight. Essentially, what the survey looks at is how the budget process is being monitored and if the checks and balances system is working in terms of ensuring accountability.

In this regard, Jayasinghe stated that Sri Lanka’s composite score for the two aspects is a 50 out of a 100, which is below the required score of 51 and below the global average score of 54. Individually looking at the performance of both legislative oversight and audit oversight, she explained that what they saw was that audit oversight, which has a score of 78, performs better than legislative oversight, which has a score of 36. She went on to state that audit oversight improved from the last cycle, which was a score of 67, while legislative oversight went down from its score of 42.

Jayasinghe attributed the improvement of audit oversight in the 2019 cycle, to the independent reviews of the audit process. As for legislative oversight, she stated that it fell because there was less time for the Parliament to examine the budget proposals and certain requirements by the committee on public finances were not made publicly available.

She recommended that there should be higher accountability for changes made to the approved Budget, and that the Ministry of Finance can strengthen oversight by consulting the Parliament before funds are shifted from its allocation in the enacted Budget.

“In cases of shifting funds between administrative units, like ministries or departments and cases where there is spending of unanticipated revenue or a reduction in spending due to revenue shortfalls, international best practices stipulate that the legislature should be consulted before shifting,” Jayasinghe explained.

Public participation

Jayasinghe stated that transparency alone is insufficient to improve governance, and inclusive public participation is crucial to realise the positive outcomes associated with greater budget transparency.

“This looks at how the public can provide their input to the Ministry of Finance, the Parliament, or the audit institution in the budget process,” she said.

In this regard, Sri Lanka has scored 17 out of 100, which indicates few opportunities for public participation in the budget proposals. However, the country has improved from the last cycle’s score of 11, and is above the global average of 14.

While countries around the world are struggling to meet the best practices in terms of public participation, Jayasinghe stated that Sri Lanka currently has numerous mechanisms to help provide public input in the budget process, such as the “citizens engagement” programme, stakeholder meetings with Chambers, and additional mechanisms as of last year.

However, she stated that when they looked at public participation in the budget stage, the country’s scores were quite weak when it came to approval and implementation. She went on to state that essentially, the country does not not have any public participation mechanisms for the public to give their input in implementing the budget, with only a few being available at the budget approval stage.

“This again highlights weak legislative oversight, because again, the legislature gets involved in the budget approval and budget implementation stage,” Jayasinghe noted.

In order to change this, she suggested that the Ministry of Finance pilots mechanisms to include the opportunity for public input during budget implementation, where the public can engage in the monitoring of budget implementation and also have mechanisms that enable disadvantaged and vulnerable communities to proactively engage with any stage of the budget process.

“Countries like Mexico, from the 2019 survey, show that they have a mechanism implemented for their budget proposals that benefit certain disadvantaged communities and there are committees established within those communities to provide feedback on the implementation of those proposals,” Jayasinghe said.